In June of 1915, as World War I blasted land and bodies apart across Europe, as German leaders were naming the conflict “Materialschlact” (the battle of equipment), Hugo Ball, the German-Swiss co-founder of the Dada art movement, wrote this in his diary: “The war is based on a crass error. Men have been mistaken for machines.”

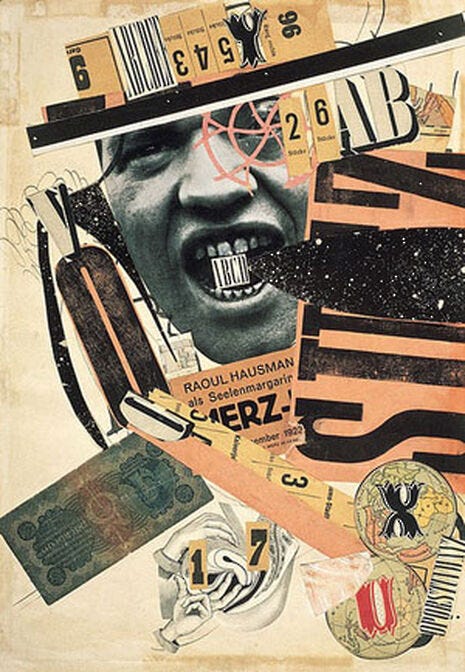

Dada artists, beginning with Ball and his friends at Zürich’s Cabaret Voltaire in neutral Switzerland, worked with chaos, fragments, and absurdity to expose and deflate this “crass error.” With the time-immemorial tools of tricksters, Dada artists resisted the war and its governing logic through hyperbolic extrapolations, chaos artmaking practices, and performative mistrust of the settled story.

This morning, having just finished the very pleasurable process of editing this 18th episode of Kinward, an interview with artist, educator, and Indigenous Futurist Rozzell Medina—who, among other pursuits, teaches a course on Dada and its continuing influence in the art of the possible—I’m thinking about the kinds of practices that can make certain kinds of stories—like the stories that say we are machines—redundant and ridiculous.

I’m thinking about this, while outside the sun is squinting through the clouds just strongly enough to unstick the hoarfrost crystals from the umbels of senesced herbs and the twig-tips of the aspen trees. Sharp white needles are falling beautifully—and audibly. I tried to get a recording, because it’s about time to change the Kinward intro sound palette from flowing water to something icier. But the hoarfrost-sifting-down sound is really too subtle for my mic.

Standing with my feet on the ground in the cold winter garden in the cold morning, trying first to fully appreciate and then to capture and then simply to enjoy the sound of this particular shape of water falling into frozen grass, feels like a tiny, daily, rooted affirmation of the true powers, a grounding for this wintery moment, in a world of activities and constraints that feel increasingly rootless, distracted, and hollow.

I’m a pretty earnest human, maybe to a fault. My usual resistance to rootlessness and distraction is to step outside and pay attention, to breathe in presence, to speak and act in alignment with what I really care about, in ways that affirm my core values, that vest me with physical health and mental clarity. So I do things like stand with the frost crystals and say, here I am, standing with the true powers. It’s great.

Meanwhile, the machine chugs on, devouring forests and shitting plastic, and when we’re tired of all the bad news at the end of the day we keep scrolling (and dying of preventable cancers and then going bankrupt).

And also meanwhile, radical artists and tricksters, bouffons and chaos magicians, have always known that it’s possible to push absurdity to an extreme that punctures the more minor illusions we’re asked to swallow every day.

There’s a lot to be learned in that, for me.

As listeners of this podcast likely know, and as Rozzell emphasizes throughout today’s conversation, “radical” literally means “of the root.” In the space of this interview, Rozzell and I consider this word—consider roots—in relation to Home, homecoming, and homelands; punk rock; the flourishes and fruits of Indigenous, African and Afro futurist cinema; the strange loops and chaos-play of Avant Garde art; and our own practices of imagination.

Rozzell Medina is a multicultural artist, musician, writer, and educator with ancestral roots in Hopi-Tewa, Mexican-American, and European traditions. He is the director of the Portland EcoFilm Festival at the Hollywood Theatre, the premiere international ecological film festival in the USA Pacific Northwest. Through partnerships with the Clemente Course in the Humanities, Bard College, and Oregon Humanities, Rozzell creates and instructs college courses on intersections of avant-garde imagination, futurisms, and socially engaged art making.

I love how the word radical draws a through-line-through this interview from the “true powers” of land and the Earth and her elemental forces—powers of which we humans, as Indigenous activist John Trudell powerfully reminds us, are also an expression—to mind-melting-and-melding experimental film; to a Gen X ethos of wildness that is sometimes smeared as nihilism; to art practices embracing generative chaos; to the many homecomings we are trying to make possible now, all around the world, for ourselves and our kids.

Rozzell and I cover quite a bit of ground in this interview, but its commitment to radical imagination for the sake of “the world’s child” feels very complete and full circle to me—especially in conversation with the Mad Max 2020 Immersion episode with Rozzell that I released back in November. These two episodes stand alone just fine, but your experience of each will be enriched by the other, I think.

Today’s episode also includes some vulnerable discussion of my parenting journey up to this point—and I am feeling vulnerable in this time of preparing to give birth to my second child (due in January). There will be one more episode in this first season of Kinward, which will air on December 30, and then I’ll be taking a maternity leave. Read more about this here, and stay tuned for Season 2 of the podcast, which will begin airing sometime in the first half of 2025.

Gratitudes for this episode include: to Rozzell, for investing himself over and over again and deeply in radical imagination; to our mutual friend JR, co-fabricator of co-created haunted houses, whom Rozzel mentions in this episode, for using their own imagination to step into their responsibilities as a grownup; to this morning’s rime of hoarfrost for the important reminder that water, always dynamic, has a particular shifting glittering dynamism in winter; and to my child and unborn child, and to children, and to “the world’s child” for their many teachings to stay in tune, to chase what’s new, and to play. And to all of you, for listening. Thank you.

Share this post